How many kinds of COVID-19 variants detected so far

Experts say new variants are not necessarily deadlier forms of the coronavirus disease but are more infectious

At about the same time the first vaccines against the coronavirus disease were being approved and acquired in December 2020, health officials in the United Kingdom announced a new strain of the virus.

The variant was initially reported to be up to 70 percent more infectious. A few days later, another variant of the coronavirus was announced in South Africa – already the country with the highest rate of COVID-19 cases on the continent at more than 15,000 a day.

And in January another variant was detected in Brazil, originating in the northern state of Amazonas, where the majority of the capital’s population has been infected.

According to Dr Deepti Gurdasani, a clinical epidemiologist and senior lecturer at Queen Mary University of London, a variant was developed in February-March last year in Wuhan called D641G.

“That variant was associated with about 20-30 percent increase of transmissibility that rapidly became the dominant variant in the world,” Gurdasani told Al Jazeera.

“This highlights the potential of this virus to adapt.”

But let’s start at the beginning.

What is a variant?

Variants are mutations of a virus. All viruses mutate when they copy themselves in order to spread and thrive. Most mutations are insignificant, some can actually harm the virus, and others can produce a variant that will make it more transmittable.

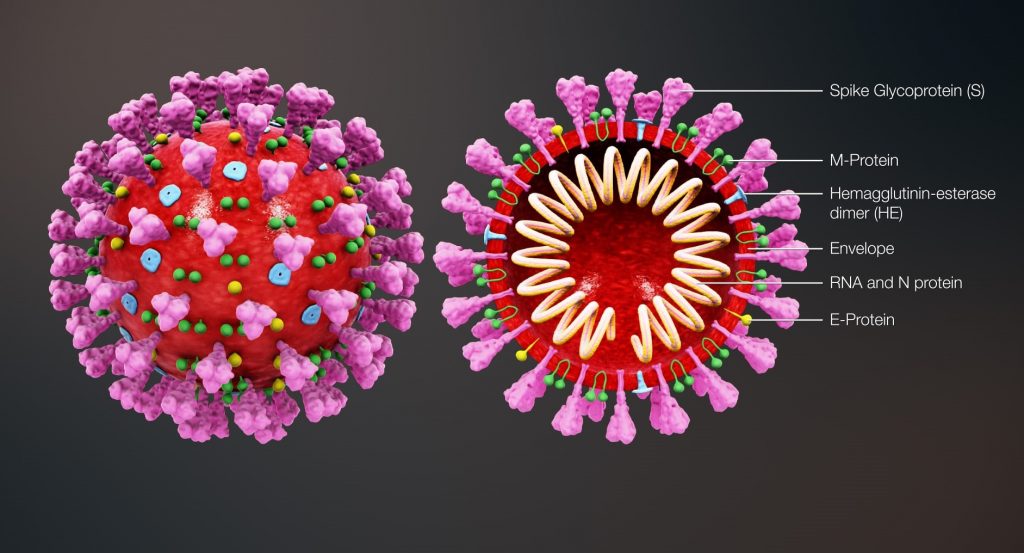

To break it down further, a mutation is a change in the genetic material of the virus – or what is called the ribonucleic acid (RNA).

A virus spreads inside the body by attaching to a cell, then entering it. They then make copies of their RNA, which helps them proliferate. If there is a copying mistake, the RNA gets changed and that is what scientists call a mutation.

Brooke Nichols, an assistant professor at the Boston University School of Public Health, said mutations occur much more frequently with RNA viruses because the RNA “has no ‘proofreading’ capacity and, as such, cannot correct the mistakes that are made during viral replication”.

“This can then become problematic when the virus then selects for mutations that allows for the virus to replicate more efficiently,” Nichols told Al Jazeera.

“For example, if a person has been previously infected, then the virus may select for mutations that can evade that previous immunity, or select for mutations that allow for the virus to be more transmissible.”

What does it mean for coronavirus and humans?

The coronavirus disease has undergone several mutations since the beginning of the pandemic.

All three variants detected in the UK, South Africa and Brazil have undergone changes to their spike protein. This is the part of the virus that attaches to human cells and makes it better at infecting cells and spreading.

Although scientists agree the mutations found in the three variants make the coronavirus more infectious, there is no evidence these actually aggravate the disease or are more likely to cause death.

“The variants do not appear to make the coronavirus disease more deadly,” Nichols said. “The variants do, however, make the virus more transmissible. This could mean that more people can become infected more rapidly- and thus still overburdening healthcare systems.”

B1351

On December 14, UK health officials reported a new variant to the World Health Organization (WHO).

The variant, called B117, was first detected in September in Kent, southeast of England. By December the strain accounted for 60 percent of new COVID-19 cases in the UK, becoming the most common version of the coronavirus.

While preliminary evidence suggests the variant may be up to 30 percent deadlier, experts say the data is limited and there is still not much information to determine how infectious it is.

It was initially reported the variant could be up to 70 percent more transmissible, but the latest research by Public Health England puts it between 30-50 percent.

Early research appears to show vaccines are effective against this variant. Last week, the Novavax and Johnson & Johnson trials showed they were 86 percent and 66 percent effective, respectively.

In late January, scientists said the Moderna vaccine trials also appear to work against the variant.

The UK strain has also been detected in more than 50 other countries, including China, India, and the United States

Recently, experts said the variant has a mutation that is present in the South Africa one – the E484K, which is thought to help the virus evade parts of the immune system and antibodies.

B11248

In the middle of January, a third variant was discovered in passengers arriving from Brazil to Japan.

The origins of the B11248 variant was traced back to the northern Brazilian state of Amazonas where it was first detected in its capital Manaus in December.

It also has the E484K mutation.

“What we know it has independent and shared mutations with both the UK and South Africa variant,” Dr Deepti Gurdasani said.

This particular variant is concerning “because in the laboratory is has been associated with significantly reduced neutralisation from antibodies directed at previous variants”, she continued.

During the first wave of the virus, 76 percent of people in Manaus were exposed to it.

“But we are still seeing huge waves of infections and it is very unclear at this point in time as to why that is,” Gurdasani said. “It could be because we are dealing with a new variant so it is more transmissible which increases the herd immunity threshold. But it could also be that this variant escapes at least for some people the immune response to the previous variant.”

The variant was present in 51 percent of samples taken from coronavirus patients in December, he said. By mid-January, it was 91 percent.

Scientists do not understand why the variant has spread so explosively in Brazil and why it carries a particularly dangerous set of mutations.

Will vaccines work on the new strains?

Mutations help the virus evade antibodies or escape recognition by them.

However, vaccines train the immune system to attack several different parts of the virus. That is, the antibodies of the vaccines target many parts of the spike protein, so even though a part of the spike has mutated, the vaccines should still offer a degree of protection.

On January 28, Pfizer said its vaccine will be slightly less effective on the UK and South African variants.

Even in the worst-case scenario, vaccines can be redesigned and tweaked to be a better match in a matter of weeks or months, if necessary, medical experts say.